Why have a stress test?

STRESS TESTS ARE FOR SYMPTOMS:

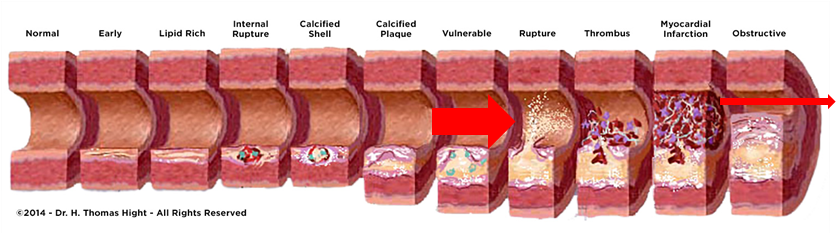

When the blood can't pass through the artery due to narrowing, symptoms like chest pain result. We call narrowing "stenosis" or "obstruction" to flow. Look at the difference (above) in the small red arrow depicting poor blood flow in obstructive disease and the large red arrow where vulnerable disease has great blood flow. Obstructive disease causes symptoms. Vulnerable arteries do not.

Designed for patients who have symptoms of chest pain or shortness of breath, stress tests are done to ask this question: Is the chest pain caused by severe stenosis, obstructing the blood flow? When the blood can't flow through the artery, stenting or bypass surgery is performed.

A screening test is a test we do when someone is having no symptoms. We do screening to find out who is at risk. Stress tests were not designed for screening to find someone at risk for heart attack, and are not recommended for that purpose (1).

Should someone with no symptoms get a stress test? Or a stent?

When there are no symptoms, stents don’t prevent heart attacks or save lives.

In spite of all the money we’re spending getting stents, one of three Americans are still dying of heart disease. That statistic has not changed since the early 1900s. The COURAGE trial, published in 2007, showed that stents are no better than medication therapy at preventing heart attacks, sudden cardiac death, or hospitalization for heart disease in patients who do not have chest pain (2). The ISCHEMIA trial (presented in November 2019) showed the same thing: in patients with no chest pain, stents do not save lives or prevent heart attacks or hospitalizations. (3) The only exception was left main coronary disease (which is rare).

Stents and bypass procedures are usually done to treat symptoms of heart disease, like angina, which is caused by obstructive plaque (see above, far right). Heart attacks happen when soft vulnerable plaque ruptures, which causes a clot, or a thrombus to form, which blocks the blood flow to the heart muscle. Most heart attacks (86%) happen to people who do not need a stent or bypass (see How Artery Disease Develops). Most vulnerable plaque is not obstructive. Vulnerable plaque is much more common.

Although these two large studies are important in re-shaping the way we think about coronary artery disease, they both describe large populations. Neither trial answered the question whether stents might save lives where obstructive lesions also contain soft plaque seen on CT angiogram. Additionally, some people have “widowmaker” lesions in the left main artery, where surgical procedures do save lives. And some people have odd symptoms like diminishing exercise tolerance or jaw pain or fatigue. Not everyone has the typical symptoms of chest pain. So each patient must be individualized in light of these two studies and other data.

if your doctor recommends a stress test:

Heart disease can sometimes cause odd symptoms like neck or jaw pain or excessive fatigue or leg swelling or nausea or sweating. It's not always the typical chest tightness radiating to the left arm. If you’re having no symptoms, then you should feel free to ask your doctor why the stress test is important. Ask about the COURAGE trial and the ISCHEMIA trial. If it's because you have a high calcium score, that's a valid reason. If it's because you've already had a heart attack or by-pass or stenting, that may be a valid (although controversial) reason. But if it's to ask the question "Are you at risk for a heart attack?" then there are better ways to answer that question. Contact us.

a Stress test can never predict who's at risk for heart attacks.

Because most heart attacks (86%) occur in blockages that are not severely narrowed, most heart attack victims would pass their stress test the day before the heart attack (4,5).

Passing a stress test does not mean that your risk for heart attack is low. It only means you don't need a stent or bypass surgery (6).

Half of men and about 2/3 of women who die suddenly from heart disease had no previous symptoms (7).

references:

A recent task force paper reviewed the evidence for screening by using EKGs, nuclear stress tests and stress echocardiograms to find coronary disease in low-risk patients with no symptoms. They found no evidence supporting the use of these methods. They failed to address the well-documented evidence for screening by using CT heart calcium scans, but they did recommend using risk calculators. Chou, Cardiac screening with electrocardiography, stress echocardiography or myocardial perfusion imaging: Advice for high-value care from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162:438-447

Both the COURAGE trial in 2007, and the ISCHEMIA trial in 2019, showed that stents don’t save lives or prevent heart attacks in patients with no chest pain. The only exception was left main coronary artery disease. Boden, William, et al. the COURAGE Trial Research Group, Optimal Medical Therapy with or without PCI for Stable Coronary Disease, N Engl J Med 2007; 356:1503-1516 DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa070829

David J. Maron, et al. for the ISCHEMIA Research Group, Initial Invasive or Conservative Strategy for Stable Coronary Disease. N Engl J Med 2020; 382:1395-1407 DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa1915922

Screening by heart calcium scans, which identify calcium scores higher than 400, are often used as the basis of further testing with stress tests even in patients with no symptoms, owing to a higher risk of severe narrowing requiring surgical procedures like stents in patients with high scores.

E. Falk, PK Shah, V Fuster, Coronary Plaque Disruption. Circulation 1995;92:657

There are exceptions. Most institutions doing nuclear stress tests have a sensitivity of about 80%. That means out of 100 people who need bypass or stent, the nuclear stress test finds 80, and misses 20. President Bill Clinton passed his nuclear stress test, and then flunked the angiography, which confirmed that he did indeed need a by-pass procedure,

Roger VL, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics-2012 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2012;125(1):e2-220